A Day One Introduction to Python#

A “bootcamp” tutorial for the absolute basics of Python in 2 parts

PART 1#

Welcome. In this tutorial, we’re going to work through the absolute basics of the Python programming language. I highly recommend reading Chapter 2 of the textbook either before, or concurrently, with working through this tutorial. It will cover much the same ground, but here you’ll get to actively practice the techniques described.

Let’s start with the concept of a declaration. In Python, our primary goal is to perform calculations - you can think of it as an extremely powerful powerful calculator, and indeed, much of what we build in python amount to pipelines that string simple mathematical computations together and perform them on data.

In order to work with more complex data than a pocket calculator (in which we type in the numbers to be computed directly), Python allows us to declare variables to store those values for later use. See below:

variable_1 = 5

variable_2 = 6

output = variable_1 + variable_2

print(output)

11

All I did was store the numbers 5 and 6 into variables (which I lazily and poorly named ‘variable_1’ and ‘variable_2’), and then computed their sum. Note: One additional takeaway here is the underscore in the variable names - you cannot have spaces in variable names, so often programmers use underscores when needed. We’ll talk later about best practices when naming variables.

You might be asking, “Why did you go through the work of declaring those variables and adding them, when you could’ve just done:”

5+6

11

In this particular case, you are absolutely right. If I wanted to know the sum of 5 and 6, I could’ve just typed it in. Indeed, even if I needed to save that output somewhere, I could’ve done

output2 = 5+6

And now, I can at any time look at that:

print(output2)

11

Or, I can use it in further calculations:

output3 = output2*5

print(output3)

55

Now might be a good time to go over the native mathematical operations available to you in Python (we’ve seen 2 so far).

addition = 5 + 5

subtraction = 5 - 5

multiplication = 5 * 5

division = 5 / 6 #be careful of Python version!!

exponentiation = 5**2

modulus = 5 % 3

What did I mean by “Be careful of Python Version” in the comment above (note: you can use comments in lines of code, via the # symbol, to leave descriptions and instructions in your code that aren’t seen or run by the interpreter).

Let’s do an experiment:

print(division)

0

Wait, that’s not right. 5/6 isn’t 0.

What we’re seeing here is a result of the datatypes we’ve been using. In Python version 2.xx (as opposed to any version of Python 3), numbers like those I’ve been using are treated as integers - the computer only knows their values to the “one’s place,” and thus finds 5/6 to be 0.

What if we want a more accurate answer? In Python 3, they resolved this issues by performing all calculations in floating point – which means including the decimial values. We can do that ourselves in a few ways:

5.0 / 6.0

0.8333333333333334

float(5) / 6

0.8333333333333334

The above illustrates 3 points. The first is that when directly typing in numbers, just adding a “.” turns the integer into a float, meaning the calculation is done correctly. The second is that you can force any integer to be a float by typecasting it using the command I showed (the same goes in reverse, you can use int(some_variable) to round what might be a floating point number to an integer. The third is that only one number in a calculation needs to be float for the whole calculation to be performed as a floating point operation - I could’ve chose either the 5 or the 6 to make a float, but only need to choose one.

Exercise 1: A simple calculation

In the box below, create 3 variables which hold your age and the ages of both of your parents. Then, set a variable named “age_average” that is equal to the average of your three ages. Be careful of order of operations! You can group operations, just like in PEMDAS math, using soft parenthesis “()”.

#your code here

print(age_average)

Data Types in Python#

So far, we have been working entirely with numbers (integers and floats). You can tell what data type a variable is at any time using the “type()” command:

x = 5

y = 6.0

print(type(x))

print(type(y))

<type 'int'>

<type 'float'>

While, at the very bottom of things, your data will always be numbers like this, Python’s power comes in when you start looking at it’s other data types, which are primarily set up to contain numbers in an organized way. Here are the basic data types in Python:

Integers

Floats

Booleans (True or False)

Lists (collections of items)

Dictionaries (collections accessed via “keys”)

Strings (contained in quotes “like this”)

Tuples (like lists, but immutable (unchangeable))

In the next few sections, we are going to learn about these data types (skipping integers and floats, which we’ve mostly covered).

Booleans#

Booleans have a one of two states,”True” or “False”. Try setting a variable equal to True or False in the box below - you should see Python “color” the word to indicate syntactically that it is a special word in Python that has a specific meaning.

true = True

false = False

true

True

These come in handy when we are employing condiditional statements (coming up below) in which we say “Hey code, if some condition is True, do “X,” else if some other condition is True, do “Y”.

Often we are using booleans without recognizing it.

Lists#

Lists are the most forgiving container in Python. Basically, we can shove whatever we want into a list, be they different data types, or even lists within lists. Of course, the usefulness of non-uniform containers becomes limited - the advantage to storing lots of numbers in a list is that you can then perform operations on them all without worrying that some won’t work.

Here’s how we define a list:

list_1 = ['a string', 5, 6.0, True, [5,6,6]]

The list above is kind of a mess - you’d almost never want a list to contain such a variety of things in it, but I wanted to highlight that, in principle, Python doesn’t care what you stick inside a list. In addition to manually specifiying what is in a list, we can use some generative functions to make lists for us when they have a regular form:

count_to_10 = range(1,11)

print(count_to_10)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

What I’ve done above is run the “range()” function, which generates a list of numbers counting up. The form of the function is range(start, stop, step), where “start” is inclusive and “stop” is exclusive (e.g. [1,11) ). If I wanted 0-9, I would do

range(10)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

using the shortcut that if only 1 argument is used, “start” is assumed to be 0 and “step” is assumed to be 1 (it has to be an integer).

Exercise 2: skip-count

Generate a list below containing the numbers 2, 4, 6, 8, … 100 and save it into a variable called skip_count. Then, below, print it to see you did it right.

skip_count =

The tutorial on Loops and Conditionals is a great place to jump to once you have the hang of what lists are and how they’re defined - that tutorial shows how we use them.

Indexing#

When we want to see what is in a list, we print it. But sometimes we want to “pull out” individual elements of a list and use them in calculations. For that, we need to “slice” or index the list for the element we want. Lists are indexed such that the first element is assigned “0” (to remember this, I got into the habit of calling it the “0th index”). For example, using the list from above:

list_1[0]

'a string'

Basically, we put closed brackets at the end of the variable name and specify which index we want. We can also pull multiple:

list_1[0:2]

['a string', 5]

Notice that the 2 is not inclusive (it pulls 0th and 1st). We can also specify a skip:

list_1[0:5:2]

['a string', 6.0, [5, 6, 6]]

So what about that list within a list? If we want a specific number from it, we can use double indexing. Also, I’ll use this as a spot to show negative indexing which lets you count backwards from the end of a list (if that happens to be easier):

list_1[-1][1]

6

What I did was pull the -1st element (final element, 2nd to last would be -2, etc), which was the inner list, and then I indexed that for it’s 1st element.

In the cell below, get it to output the "s" in "a string" in the 0th element of the list. (It works the same way).

#your code here

Dictionaries#

Dictionaries are like lists, but rather than indexing them by element number as we were doing above, we index them by a special “key” that we assign to each “value”. For example:

ages = {'Sam':5,'Sarah':6,'Kim':9,'Mukund':17}

ages['Sarah']

6

Dictionaries are inherently unordered - the order I define things within the dictionary doesn’t matter, only that I know the key associated with each value. For some applications, this has advantages over a list. Here, if I were storing the ages of students in a class and was only interested in things like the average and median age, a list would be fine. But if I needed to know who was which age throughout my analysis, a list would require me to impose that the order went “sam, sarah, kim, mukund,” and to remember that order when indexing, and if the order in the list changes, keep track of those too.

Strings#

We’ve already seen strings used - It lets you store things like words (or, later on, filepaths) in your code that otherwise don’t have meaning as far as Python is concerned. Strings are the most forgiving data type of all; you can stick literally anything inside. If you have a data file with tons of different types of data in it, Python will often just read in everything as strings and let you work out how to convert the proper things into ints, floats, etc. Strings are iterable - they can be indexed like lists, character by character.

Tuples#

We don’t use them to often, so just check out this example and follow aloong!

example_list = [1,2,5]

example_tuple = (1,2,5)

example_list[0] = 2

print(example_list)

[2, 2, 5]

So I’ve successfully defined it as a tuple and list, and changed the 0th entry of the list. But what if I try on the tuple?

example_tuple[0] = 2

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-35-33fef9f1448c> in <module>()

----> 1 example_tuple[0] = 2

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

Thus, I get an error. So basically, if you make a list-type item and want to make sure it can never be adjusted in your code, you can make it a tuple.

For more examples of the basic manipulations you can make to these basic data types, check out Chapter 2 of the textbook, which lays some of them out!

Exercise 3: Bringing it together (kind of)

Let’s try a single, longer example that (tries to) bring in the things we’ve seen above. You’ll find that part 2 of this bootcamp covers things like iterating/for loops and conditionals, which drastically increase what you can do with Python. Nevertheless, here’s some practice with the basic operations.

Let’s say you’re the teacher of your school’s introductory Quantum Mechanics class. You’ve just graded their first midterm, and are shocked, (shocked) to see so many low scores (You thought the midterm was totally reasonable!)

Before you post their individual scores, which might give some students a heart attack, you decide to calculate the distribution statistics of the exam first, so that each student can compare their score to the average, etc.

The scores are (out of 120): 100, 68, 40, 78, 81, 65, 39, 118, 46, 78, 9, 37, 43, 87, 54, 29, 95, 87, 111, 65, 43, 53, 47, 16, 98, 82, 58, 5, 49, 67, 60, 76, 16, 111, 65, 61, 73, 63, 115, 72, 76, 48, 75, 101, 45, 46, 82, 57, 17, 88, 90, 53, 32, 28, 50, 91, 93, 7, 63, 88, 55, 37, 67, 0, 79.

Your first step to analyzing these numbers should be to put them in a list (call it “scores”). Do that in a cell below (you can copy and paste from above, just add the list syntax).

scores = #your code here

Exercise 3.1

Now, the first thing we need to do is calculate the average score. Later on, we’ll see that there are external functions you can import into Python that will just do this for you, but for now let’s calculate it manually (it’s easy enough, right?).

Above, we saw use of the sum() function - as it turns out, you can run the sum() function on a list (so long as it only contains numbers) and it will tell you the sum. The only other thing you’ll need to calculate the average is the len() function, which returns the number of elements in a list/array. Using those two, define a variable below called “average_score” and calculate it.

average_score = #your code here

average_score

Exercise 3.2

Great, so we now know what the average score on the test was. Let’s figure out what that is in percent. In the cell below, calculate the percentage value of the average score by dividing it by the number of points on the test, and mulitplying that by 100 in the same line. Then, run the cell - you’ll see a nice sentence output that lists the percentage, take a look at the line I wrote that does this and see if you can glean how it worked.

avg_score_percent = #your code here

shortened = str(avg_score_percent) #turn it into a string

statement = f"The average score on the test was a {str_version:.2f}"

print(statement)

Okay, so the other thing students are always interested in is the standard deviation from the mean - this basically will tell them whether they get an A, B, C, D, or F on the test assuming you curve. Let’s be nice, and assume we are going to curve the average to a flat B (85%). The formula for a standard deviation is $\( s = \sqrt{\frac{\sum_{1}^{N}(x_i - \mu)^2}{N-1}} \)$

where \(\mu\) is the average and N is the total number of scores.

We already know how to get N, and we know what \(\mu\) is as well. So to calculate this, we need to know how to calculate the quantity on the top of the fraction. This is actually kind of tricky with the methods we have on hand, so I’m going to introduce a new concept: Numpy (numerical python) arrays. I’m going to get into these in detail in part 2 of the bootcamp, but for now, see the example below for elucidation on why we’re about to use them:

import numpy as np

arr_version = np.array(scores)

print(scores-1)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-70-b292ed98c843> in <module>()

1 import numpy as np

2 arr_version = np.array(scores)

----> 3 print(scores-1)

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for -: 'list' and 'int'

Okay, so I can’t subtract an integer from a list. What if I try the array version?

print(arr_version-1)

[ 99 67 39 77 80 64 38 117 45 77 8 36 42 86 53 28 94 86

110 64 42 52 46 15 97 81 57 4 48 66 59 75 15 110 64 60

72 62 114 71 75 47 74 100 44 45 81 56 16 87 89 52 31 27

49 90 92 6 62 87 54 36 66 -1 78]

If you look, you should see that each of those scores is the original score with one subtracted off it. Your spidey senses should be tingling then for how we can leverage this functionality to calculate our STD. In the cell below, fill in the variable I’m calling “top_frac” to calculate this quantity: $\( \sum_{i=1}^N (x_i - \mu)^2 \)$

Notice here that you don’t have to actually calculate it one by one - if we first compute a single array that represents each score with the mean subtracted off and then that value squared, then we finish off top_frac just by summing up that array as we’ve done before.

Exercise 3.3

Calculate the quantity on the top of the fraction, and then the standard deviation of the scores.

top_frac = #your code here

print(top_frac)

With that done, we can easily apply the formula to get the final STD - Hint: the function np.sqrt() will be useful here.

STD_scores = #your code here

print(STD_scores)

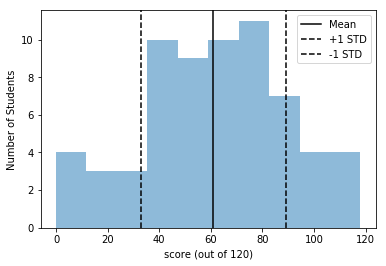

Alright! If you’ve done everything correctly, you should have found that the average score is a 61/120, with a stadard deviation of 28. Let’s, for fun, make a helpful plot to show the students their scores. Don’t worry about how the plotting stuff works just yet, we’ll dive into it more in part 2, but see if you can figure out what each part of the command is doing.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

plt.hist(scores,alpha=0.5)

plt.axvline(61,color='k',label="Mean")

plt.axvline(89,ls='--',color='k',label="+1 STD")

plt.axvline(33,ls='--',color='k',label="-1 STD")

plt.xlabel('score (out of 120)')

plt.ylabel('Number of Students')

plt.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x1099876d0>

Nice! It looks like our formula for standard deviation successfully describes the original distribution of scores pretty well. Now, how to get them to do better on midterm 2….

Wrap up#

I hope this super-basic introduction has given you a glimpse at some of the basic functionality of Python. Of course, Python is way more powerful than what has been shown here. I call this Part 1 because once you know the basic data types, how to define variables, and do some simple math on them, we are going to need to jump into new concepts — for loops and conditional statements, as well as invoke new libraries (like numpy and matplotlib) to do make further progress. If you’re ready to do that, head on over to Part 2!